An article touting the new Canadian Christmas special, A Cosmic Christmas.

I purchased an old insert from the Toronto Star’s ‘The Canadian’ focussing on ‘A Cosmic Christmas’. This is the December 3rd, 1977 issue, and would have been released at the time of the special’s Canadian television premiere.

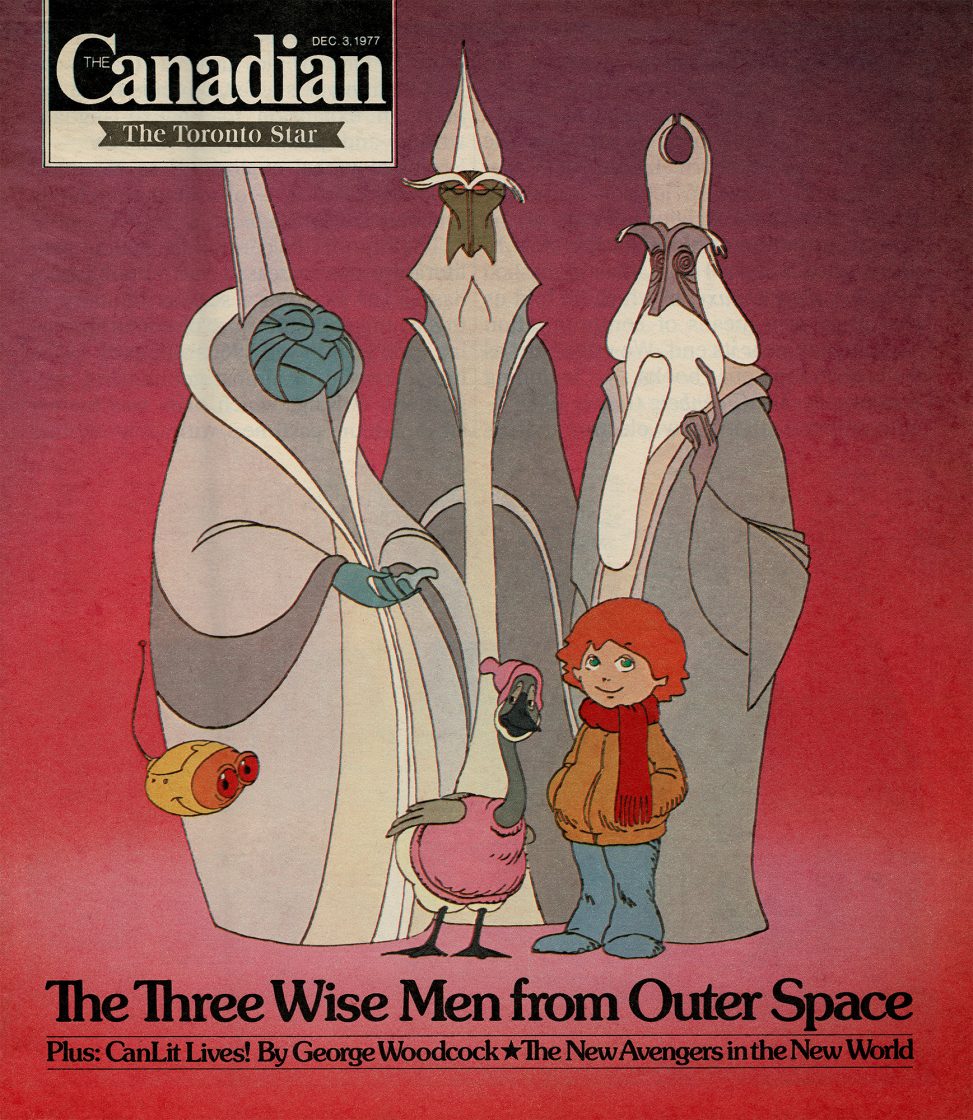

Text: The Canadian/The Toronto Star – Dec. 3, 1977

The Three Wise Men from Outer Space

Plus: CanLit Lives! By George Woodcock • The New Avenger in the New World

1977: A Space Odyssey

In which the author meets three wise aliens and their Bionic Pet.

By Robert Thomas Allen

At 7:30 next Tuesday evening in Canada, Wednesday in the United States, TV viewers will see a Canadian-made animated film called A Cosmic Christmas, a lively modern fairy tale that includes enough science fiction to fascinate the kids, spoofs it enough with an old-time Christmas here on earth, with rousing all-out carols and some lovely music composed and sung by Sylvia Tyson. Animated-film fans who haven’t missed a major cartoon since the heyday of Disney consider it one of the best, if not the best, ever to have been made in Canada.

I’ve never been much of an animated cartoon fan and when I’d first heard of Cosmic Christmas I’d had visions of all the things that, in the old says before smoking in theatres, used to send me out to the lobby for a last cigarette before the real picture started – the chases with feet screeching like tires, the characters getting flattened paper-thin by falling rocks, cats going through solid walls, leaving their outlines in broken bricks.

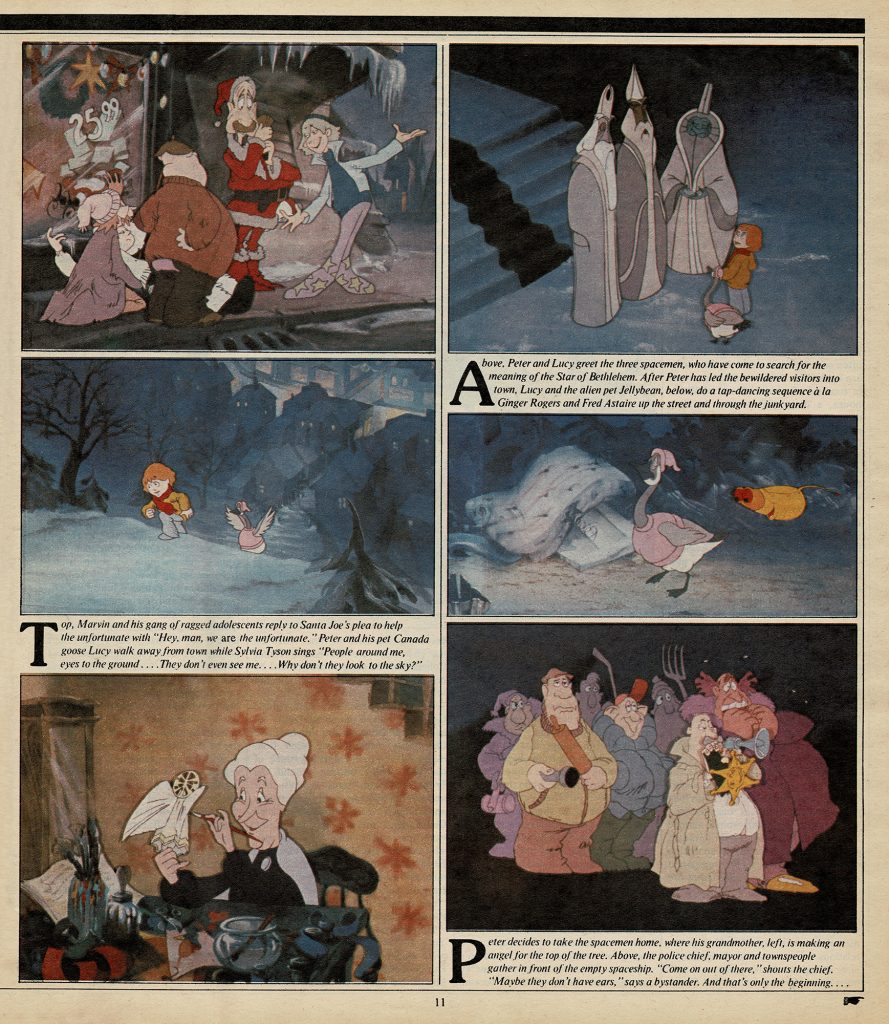

But Cosmic Christmas isn’t like that. I enjoyed it from the moment the titles appeared (“Sundown over the Western Hemisphere,” the script reads. “Camera sees the earth approaching through the porthole of what is evidently a spacecraft… The only sound is a soft wind rushing, as we see the lights of a small earth town at dusk.”) Down there a youngster names Peter is trying to get people to look up. “Look, look everybody… look at the light in the sky… but I saw it. It’s up there,” while everyone is in a frenzy of Christmas shopping, too busy to take notice.

There’s a windbag of a politician; the police chief (who later flashes his identification and calls to the aliens through a bullhorn to come out, “I’m going to count to 10”); a wonderful nasty little girl grabbing things off counters, “I want one of those and one of those and one of those” (Mother: “Isn’t she terrible?”); stately organ music when the three aliens step out of their craft, and one walks over and tries to shake hands with a tree. “We are equipped to identify, comprehend, and speak all languages known. Hello. How do you do? I am fine.”

And there’s a great dance by Peter’s pet goose, Lucy, who wears a little wool toque, and a sort of Bionic Pet, a friendly little fellow built like a cordless electric razor, the two of them doing a Shuffle Off to Buffalo routine to old-time thumping honky-tonk piano music.

In one scene, Peter and Lucy hike out into a moody winter forest and slide around on some thin ice, and this is pretty much what the producers of A Cosmic Christmas, Michael Hirsh and Patrick Loubert, did throughout the financing of the film. They figured it would cost, $165,000, most of which was covered by pre-sale to the CBC and by investors’ money raised by a partner in the firm, a young Toronto lawyer named Jeffrey Kirsch. But they eventually found it was going to cost $275,000.

While about 10 animators were producing the film at the laborious rate of 75 seconds of animation a week, Hirsh and Loubert were showing sample sequences trying to get buyers, signing notes, running up credit with suppliers, mortgaging their studio, and ignoring discouraging, and sometimes baffling, advice. They were told they shouldn’t have started it without pre-selling it – told that by men who said they wouldn’t buy anything without first seeing it.

U.S. networks, advertising agencies, prospective sponsors who look on peace, love, angels and Christmas like any other product, say, coffee beans, told them they should have stuck to something easily recognizable, maybe Charlie Brown’s or Kojak’s Cosmic Christmas, and besides, they said, viewers would think it sacrilegious having three wise men come from outer space. One veteran New Yorker sounded a bit like a biblical character himself. “Who is this Peter?” he asked Hirsh, meaning that viewers wanted characters to be immediately familiar, like Santa Claus and his reindeers. He also came up with a great idea for a final scene, a shoot-out between Santa and the space aliens which, fortunately, in spite of the fact that they were going broke, Hirsh and Loubert resisted, along with all other suggestions that would have resulted in the kind of film they didn’t want to make. “If it hadn’t been sold.” Loubert says now, “we would have lost the studio and everything we’d worked toward for over six years.”

The studio is called Nelvana, after an old Canadian wartime comic book by Adrian Dingle about Koliak the Mighty who had a beautiful daughter Nelvana, often seen by human eyes in the norther lights. The studio occupies a warren of rooms in Toronto’s Terminal Warehouse, a dingy yellow-ochre building down on the docks that smells like fish and cheese, but costs only $2.50 a square foot of floor space, compared with $8 to $10 in buildings uptown that don’t smell of fish but make it harder to keep costs down. When I visited the studio it was in a stage between the mopping up after A Cosmic Christmas and the beginning of a new film, The Devil and Daniel Mouse, for Halloween. The 40,000 final drawings that went into A Cosmic Christmas were stored and stacked in cartons in the corridor and the thousands of preliminary sketches were files in various places. Walls were covered with scribbled notices: “Mixed paint on hand – Mayor’s shirt… Grandma’s pink dress… Jean Claude’s collar and trim,” and names of characters, reminding me of those notice boards in offices showing whether salesmen are in or out, Dan Mouse, Pawnbroker, Rat, Skunk Manager – and with paintings of stumps, forests, lizards, mice, waves, clouds, fat devils, thin spooks.

The place smelled pleasantly of paint; paint was splattered on tables and stools and drawing boards. There were shelves full of paint in cans, bottles, yogurt cartons. A man in a plaid shirt, with long red hair tied at the back, was coloring a devil. A patient young woman named Lenora Hume tried to explain to me an absolutely incomprehensible animation camera that photographs the transparent acetate sheets on which the figures are finally painted.

Some of the animators at Nelvana had gnome-like looks, as if standing in deep grass, or under mushrooms. “They’re marvelous at a party,” said a public relations woman names Judy Doyle, busy slicing cheese for guests who had been invited to a screening of A Cosmic Christmas. “When they get tight they get more and more like their characters.” Animators do identify with the characters they’re working on, acting out gestures before mirrors, and sometimes making faces and gestures at one another. They make sketches of people on subways and buses and at parties, where they’re apt to hand guests a sketch of how they look getting the pepperoni off a pizza.

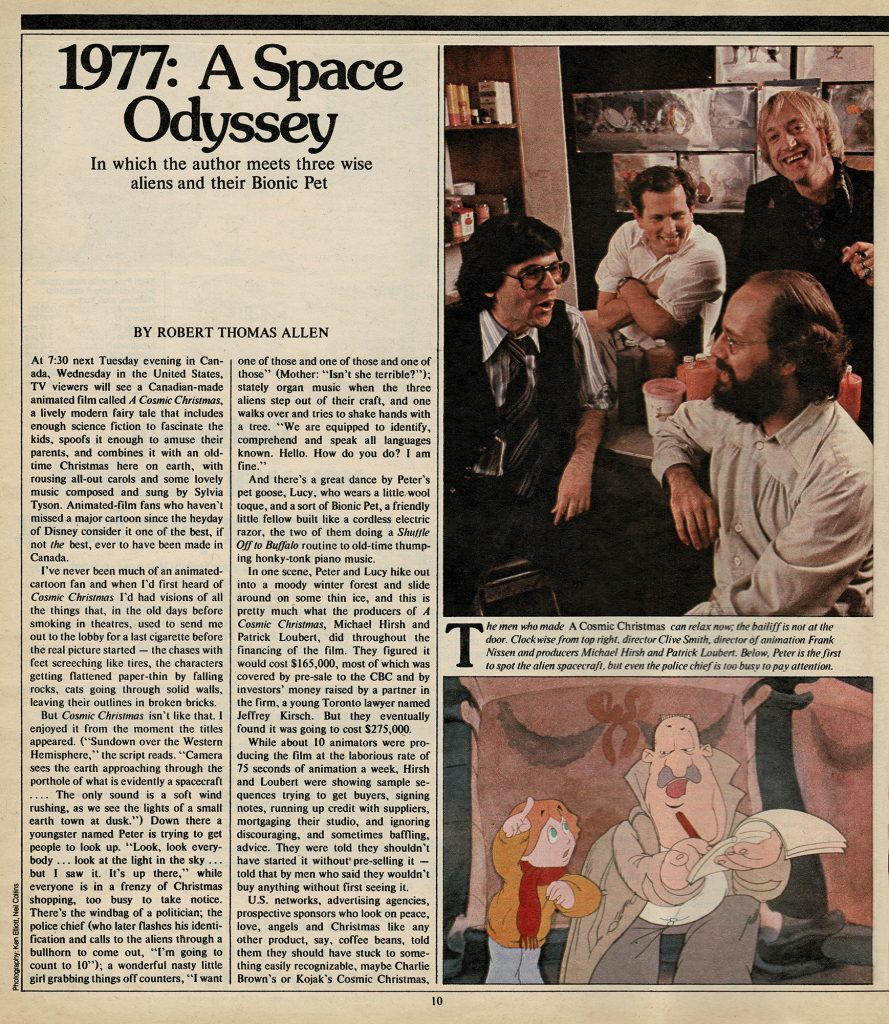

I talked to the director of Cosmic Christmas, a former Londoner named Clive Smith, and black-bearded Frank Nissen, the director of animation and layouts, two of the key men with Nelvana. “Animators have a sense of whimsy,” Nissen said. “They can play with reality. The can make an apple falling out of a tree into an angry apple or a happy apple. They can make a dragon friendly or horrible.” But this is not a surface knack of drawing. “An animator can deal with things that go beyond reality, but it comes from observing life, and knowing how people express certain things – what they do when they’re sad, when they’re surprised or happy. Animators have to do their homework if they’re going to bring eloquence to their work. You may want to make a happy teacup dancing. You have to know dancing, happiness – and teacups.”

Michael Hirsh and Patrick Loubert, working together or on separate projects, have turned out an impressive number of documentaries and educational programs for Canadian television, using live actors or animation or both, and on a variety of subjects, from children’s shows to films on topics like energy management. Both of them became interested in film while still going to school. Hirsh, a relaxed, loose-limbed man of 29 with a mop of jet-black hair, was born in Brussels, Belgium, and raised in Toronto’s downtown ethnic district, where his family moved when he was 3. When he was 13 his family moved to New York and Michael went to school in the Bronx where his fellow students made up for an appalling lack of knowledge (some didn’t know New York was on the ocean) by occasionally beating up the teacher, whom they addressed as “Hey Teach!” He later went to the Bronx School of Science, but was already becoming interested in film. When he was 16 he discovered that nearby Hunter College showed campus movies and he began spending more time there than in science classes.

He had a friend, Elia Katz, whose father had walked out on his family but had left an 8mm camera. Michael and Elia began making films, their first, called Abe and Issie, consisted largely of the two youths walking around the Bronx Zoo with signs around their necks. The thought it was a great film and arranged a screening at a place called Cinématique, where it was judged the worst movie ever made. “But the man who said that made really bad movies,” Hirsh recalls. “We took it as a compliment and were encouraged to continue.” He sometimes used professors as actors: “You could get excellent grades when you had a professor acting in your film.”

He returned to Toronto and went to York University, majoring in philosphy, made 21 more films, and met Patrick Loubert, who was majoring in English but like Hirsh was interested in making films and getting students to take part in them. When they left school they joined a Toronto firm called Cineplast, which made animated films for the children’s program Sesame Street. During a slack period, when the management put the two men to work painting the company’s building, a house in mid-Toronto, they decided to go into business for themselves. They called their company Laff Arts (later reorganized into the properly set-up company Nelvana Limited), raised some credit at the bank branch where they had their personal accounts, had business cards printed, and began operation in the basement of a house near the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Until then casual dressers, Hirsh and Loubert decided they’d better start looking the part of businessmen. From the Salvation Army they bought some clothes that their first startled customers have since described as “early 1940s gangster.” A man with Film Arts later told them, “I couldn’t believe it when you first walked in the door.”

Loubert is a tall, erect man of 30 with a pink complexion and the energetic appearance of someone who just came in off a ski slope. He had intended to fo through for law and worked one summer as a junior clerk in a law firm, collecting money from people who, he felt , couldn’t afford to pay it. He hated it, particularly the part where he had to serve the summons by tapping the debtor on the shoulder with it. He got the idea for A Cosmic Christmas at 3 o’clock one morning when his friend Judianne sat up in bed and looked out the window of Patrick’s house on Toronto Island and saw something like a cluster of lights hovering over Lake Ontario. “I got dressed and went out to look at it,” he says, “but by the time I got there I couldn’t see it anymore. But I swear I saw it. It wasn’t moving. It was dead still.” That night strange sightings were reported down into New York State, and the next day Loubert had worked out an outline for a story.

Nothing could induce me to give away the whole plot of the film, but it involves a lot of fun and excitement, and a tense rescue scene. I became an unabashed emotional pulp of pleasure during the swelling chorus of Partridge in a Pear Tree, and nearly waved goodbye when the aliens took off, formed a big angel in the sky and turned into an Unidentified Flying Object, or a planet, or a star. I came out of the screening room beside a stunned-looking little boy and a woman in a gaucho suit to laughed, blinked, looked embarrassed and said, “That was a tearjerker.” I went home with the Scrooge in me softened to the texture of warm plasticine, noting how the sun shone on old bricks, beaming on rude bus drivers, and humming “Why, oh why, don’t they look to the sky?”

Leave a Reply